Hello runner friends!

Welcome back to the Bass Pro Fitness Series

MIDWEEK M😊TIVATI😊N blog!

Now let's get started by talking about what we can learn from Eliud Kipchoge, the world's fastest marathoner who

broke his own world record Saturday by crossing the finish line of the Berlin Marathon in 2:01:19. "Limits are there to be broken," Eliud tweeted afterwards. "By you and me together. I can say that I am beyond happy today that the official world record is once again faster. Thank you to all the runners in the world that inspire me every day to push myself."

And while the limit Eliud set out to break is unattainable for all but the elite, each of us has personal limits--whether it's qualifying for Boston, setting a new PR, shaving a few minutes off a half-marathon time or simply finishing a race without feeling like you've been hit by a truck-- that can be broken by adopting some of the training habits Kipchoge has. So without further adieu, check out these

six principles Eliud regularly practices.

For Kipchoge, recovery runs start at a shuffle, typically an 8:30-to-8:45-minute-mile pace, and slowly build up to finish around 6:30 to 7 minutes per mile. That’s starting at four minutes per mile slower than his marathon pace, and still two minutes per mile off his marathon pace at the end. The goal here is to build overall volume—Kipchoge runs 124 to 136 miles each week—and ensure he’s ready to run fast for his next workout.

Though challenging, the workouts are controlled. “I try not to run 100 percent,” he says. “I perform 80 percent on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday and then at 50 percent Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday.”

Balance the Body

Twice a week, Kipchoge and his training partners perform a 60-minute session of strength and mobility exercises using yoga mats and resistance bands. The exercise program focuses on the posterior chain, particularly the glutes, hamstrings, and core muscles. It involves a series of glute abduction moves using resistance bands and the athletes’ body weight: bridges, planks, single-leg deadlifts, followed by proprioception and balance exercises and some gentle stretching to finish. He doesn’t lift weights, and the goal behind these exercises is chiefly injury prevention. “The exercises are not something where you suffer,” says Marc Roig, the physiotherapist who oversees the routine. “The idea is that you’re not crushed. The idea is to create a very basic balance in the body. We know the important part is running, so we want to complement [it] a little bit and avoid any negative interference.”

For Kipchoge, every day starts at 5:45 A.M., and he’s in bed by 9 P.M. each night. During the day he’ll nap for an hour, while his spare time is spent reading or chatting with his teammates at the camp. Despite the many demands on his time, he’s very, very good at doing nothing. Kipchoge drinks three liters of water each day and has worked with a nutritionist in recent years to improve his diet, mainly to include more protein. His meals are simple: homemade bread, local fruits and vegetables, lots of Kenyan tea, some meat, and a generous daily helping of favorite food—ugali, a dense maize-flour porridge. When it comes to supplements, Kipchoge told me he takes none. He gets a massage twice a week with his physiotherapist, Peter Nduhiu, who has worked with him since 2003. “He’s been one very lucky guy,” Nduhiu says. “He hasn’t had injuries, but he makes it easy for me, because he follows what the coach says. If you’re managing an issue and tell him to slow down, he does exactly that.”

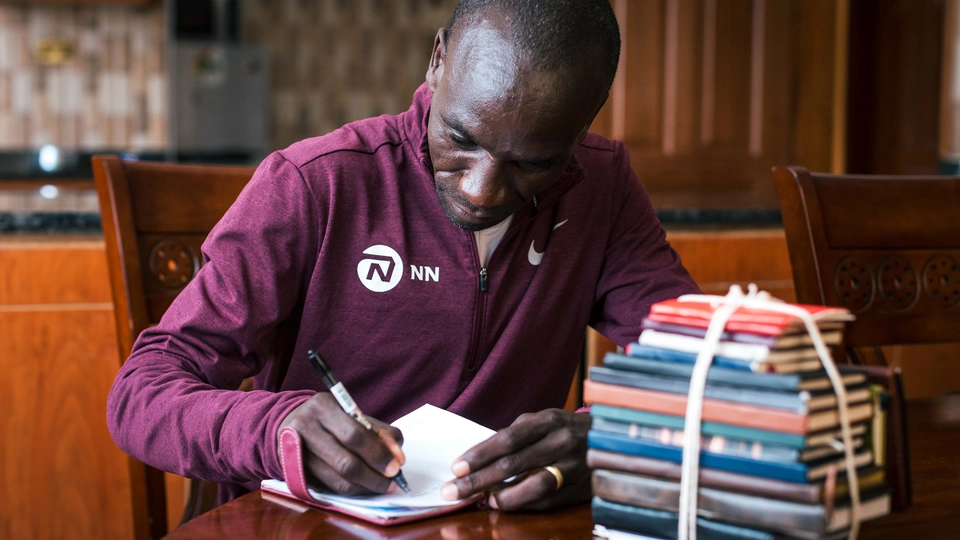

For most runners these days, recording workouts happens automatically via their watch, but Kipchoge still follows an old-school approach, logging every detail in a notebook. He began the practice in 2003 and now has 18 logs stored at his home to reflect on at the end of each season. “I document the time, the kilometers, the massage, the exercises, the shoes I’m using, the feeling about those shoes,” he says. “Everything.” He is known to review these details and learn from them for future training cycles. And they make a remarkable record of marathoning excellence. “I trust one day I will go through them and see what has been happening in the whole system,” Kipchoge says. “When I call off the sport, I will combine them and write about them one day.”

Let Your Pace Progress Naturally

“What’s the biggest mistake marathoners make?” I ask Patrick Sang, who has guided Kipchoge’s career for more than 20 years. “Not listening to their bodies very well,” he says. “And not understanding what they are supposed to do.” Sang likes his athletes to monitor effort—not with GPS watches or heart-rate monitors but by feel. When it comes to long runs, he doesn’t ask for a specific pace but an effort that’s controlled yet challenging, the pace naturally increasing each week as fitness builds. Sometimes runners who join the group will head off at a crazy pace and mess up the other athletes, Sang says. On each run, the pace should get progressively faster, or at worst stay the same. Forcing the pace beyond your fitness does no good. If you hammer the first half of a long run but can’t maintain it to the end, Sang says, “You’re on my list.”

After each marathon, Kipchoge takes three to four weeks completely off before beginning a three-to-four-week preparatory phase, during which he alternates an hour of strength exercises and step aerobics one day with an hour of easy running the next. When he shows up at camp, ready to begin his specific marathon training, Sang often has him do a set of 3K repetitions on the track to gauge his fitness. Then it begins: the hard-easy approach that sees Kipchoge run fast three days a week and coast through the rest of his runs, sometimes at a comically slow pace. His marathon-training blocks have been as long as seven months and as short as three months, but typically they last around 16 weeks.

So there you have it friends. Pick your goal. Train hard. Always keep a positive attitude. And above all, don't forget to smile like Kipchoge. Science not only backs up his belief that a smile lessens a person's perception of pain and fatigue thereby increasing performance, but you'll have much better finish line photos. And who doesn't want that right? Happy Running!